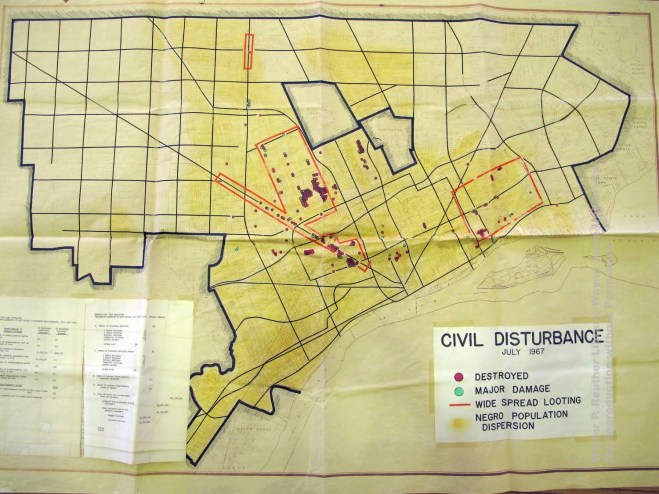

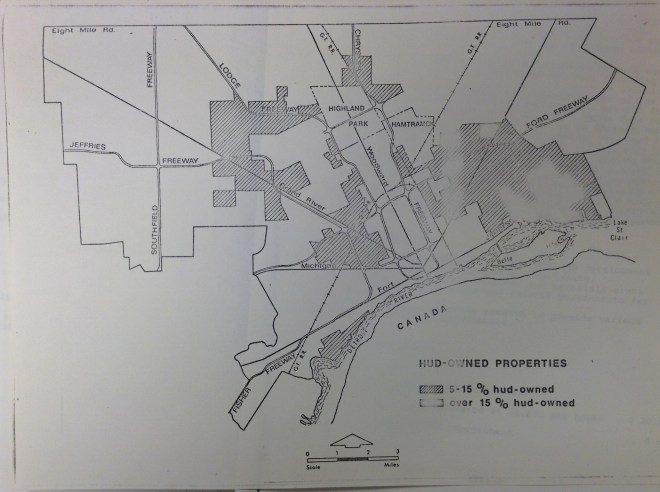

For nearly four decades, speculation in the lower Cass Corridor wreaked havoc on residents and shredded the community fabric that held it together. By the early 2000s, the area was largely deserted except for low income apartment buildings. The primary speculator in this neighborhood was the Ilitch family, the owners of a national pizza chain and two major sports franchises. The Ilitch companies bought the first property in the area in 1982, the same year they purchased a hockey team. The subsequent purchases in the 1980s and 1990s, and the intentional neglect of these properties, made it easier to acquire larger numbers of parcels. The competition among speculators increased as it became clear that the lower Cass Corridor was likely the site of a new hockey arena, but those bets on a future development meant there was little incentive to maintain properties in the area.

Meagan Elliott examined the consequences of this type of speculation in her 2018 dissertation, Imagined Boundaries: Discordant Narratives of Place and Displacement in Contemporary Detroit. Elliott’s research focuses on both the process of displacement and residents’ experience of it. She details how city government, quasi-public agencies like the Downtown Development Authority, and wealthy and politically connected developers such as the Ilitches work together. Even more important, her work explores the dissonance of residents’ experience in a multi-decade process of destruction in the lower Cass Corridor.

Elliott captures a type of displacement that is often missed in academic work on gentrification and neighborhood change. Essentially, how some speculators/developers manufacture the gap between current value and potential value through a strategy to acquire and then blight. In her interviews in the lower Cass Corridor, residents told Elliott they believed the Ilitches were responsible for waves of vandalism that left broken car windows but no theft that further destabilized the community. Whether or not the Ilitches were directly involved, these longtime residents had a clear understanding of who was to blame for the creeping decline in their neighborhood.

In this case, speculation operates as a long term development practice. The multi-decade process of intentionally devaluing a neighborhood that makes property acquisition cheaper and eliminates obstacles to redevelopment plans. Basically, redevelopment becomes the only option after decades of destruction in a community.

The Ilitches recently opened an $863 million hockey arena in the lower Cass Corridor. It is surrounded by a sea of parking lots. The Ilitch family claims these lots will eventually become “The District Detroit,” a set of five off the shelf urban neighborhoods. Detroit has heard this story before, 25 years earlier when the Ilitches used public money to build a new baseball stadium. The promised entertainment district never materialized. Instead there are a sea of surface parking for events. A revenue generator for the Ilitch’s, but not much else.

The Ilitches appetite for public funding is only rivaled by public officials’ willingness to find increasingly creative ways to give it to them from signing over concession revenues in city-owned venues in the early 1980s, to cobbling together multiple downtown blocks to hand over to the family, to financing a baseball stadium, and a large portion of the hockey arena. The last give away came while the city was in bankruptcy.

The public subsidy of stadiums is always an economic loss for cities (cite). In Detroit, citizens were ahead of the curve in the early 1990s passing an ordinance to prevent public financing of stadiums. Less than five years later, the Detroit City Council overrode that ordinance and then handed over $283 million to the Ilitch family to build a downtown baseball stadium. Less than 25 years later, government officials were ready to try again providing nearly $500 million in incentives for the hockey arena.

Meagan Elliott’s dissertation can be found here:

https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/handle/2027.42/144123

Further reading on the property practices of the Ilitches or its appetite for public money:

https://deadspin.com/mike-ilitch-was-no-saint-1792480558

https://www.metrotimes.com/detroit/how-mike-ilitch-scored-a-new-red-wings-arena/Content?oid=2201553

https://www.guernicamag.com/joshua-akers-and-john-patrick-leary-detroit-on-1-million-a-day/