by: Joanne Coutts

Place names are an enduring and omnipresent way of remembering the past. The choice of place names informs whose version of history is commemorated and given precedence today, and in the future. Our daily interaction with the names of streets, parks, rivers, and buildings continuously reinforces a specific version of history and consciously and subconsciously informs our relationship to the places we live.

A Brief History of Place-Naming in Michigan

People have been naming places for as long as there have been people in places. Indigenous place names often relate to the intrinsic nature of the land. Teuchasa Grondie, the place of many beavers, is the place name Iroquois speakers call the place we call Detroit, and Maskigong, based on Ojibwe “mashkig” meaning “swamp,” describes the large wetlands at the headwaters of the Maskigong Ziibi (Muskegon River). Descriptive place names value the land for its innate properties and allow for the creation of practical maps that share knowledge of how to get from one place to another, using narrative stories, poetry, and song, as well as pictorial images.

Settler-colonialism brought with it the practice of naming places to claim land ownership. British, French, and Spanish colonizers asserted the collective ownership of their rulers and cultures through naming places for kings and queens, Christian Saints, towns and cities, and famous figures from their history. Hence across the river in Ontario there is a town called London and a river called Thames, and any number of places across the U.S. named for St. _____ and various Charleses, Marys and Georges.

Individual colonizers claimed ownership of land by affixing their names to the places they settled. To give just two of many examples in Michigan; Pellston was named by William Pells in 1882, to claim his ownership of a camp on the Grand Rapids and Indiana Railroad (Petoskey News Review, 14 April 1966), and on the Lake Michigan coast, Bliss was named for Rhoda Bliss, the first white woman to colonize there (The Petoskey Record, 19 September 1883). Many of the places the colonial settlers slapped their names on already had names. Some of these names were erased and replaced, such as Teuchasa Grondie by Detroit, and some were erased and colonized by language, for example, Maskigong to Muskegon, Michigami to Michigan, and Michinimakinaang to Mackinaw.

Later settlers stole not only Anishinaabe land but also Anishinaabe language to name places. Peter White, iron mining tycoon, appropriated the Anishinaabemowin word “ni-ga-ni” meaning “he walks foremost or ahead,” and anglicized it to Negaunee, to name a colonial settlement on the Upper Peninsula in honor of the “pioneer” ore furnace in the region. Henry Schoolcraft, US “Indian Agent” in Michigan, who incidentally has a street named after him in Detroit, made up place names by combining Anishinaabemowin and Latin. For instance, Arenac is a combination of Latin “arena” meaning sand and Ojibwe “ac” meaning land or earth made up by Schoolcraft to mean “sandy land” or “sandy place.” Some other Schoolcraft appropriated names include Alcona, Alpena, Iosco, Kalkaska, Oceola, and Oscoda. Before assuming that a place name is Indigenous in Michigan it is worth researching to ensure it was not made up by Henry Schoolcraft.

Place naming for individuals did not just rename the land, it redrew the map. Instead of explaining, verbally or pictorially, how to get from A to B by describing the features of the land, maps now facilitated navigation using the names of the local colonizers. This orientation around ownership claims removed a layer of connection to the land as people walked or rode along the path navigating, not by the wetlands at the headwaters of the river, but by Pells’ Railroad Camp.

Redrawing the map also erased and rewrote history. Many books, blogs, historical societies, websites, and Wikipedia posts have been dedicated to the stories of settlers who named places for themselves. All these sources, directly or indirectly, legitimize colonizers’ land ownership claims and orient us to place from a settler colonial perspective. Trying to dig beneath the layers of William Pellses, Rhoda Blisses and Arenacs to learn the original place names and the stories of the people who called them home is not an easy task.

A New Gazetteer for Downtown Detroit

To visit downtown Detroit to be immersed in a space created to laud a specific version of the city’s past and perpetuate a vision of the future where that vision is seen to be the natural, and only possible, order of things. This space is created using monuments, statues, parks, fountains and, most ubiquitously, street names. In his work on the naming of Martin Luther King Jr. Streets in the Southern US, Derek Alderman notes that, “Naming is a powerful vehicle for promoting identification with the past and locating oneself within the wider networks of memory” and, “[street names] make the past intimately familiar to people in ways that other memorials cannot.”

What does it feel like to move through a land where your place names, language and history have been erased or ignored? For People of European Descent with our language and history so prolifically and seemingly indelibly inscribed on the land, it is almost impossible to imagine.

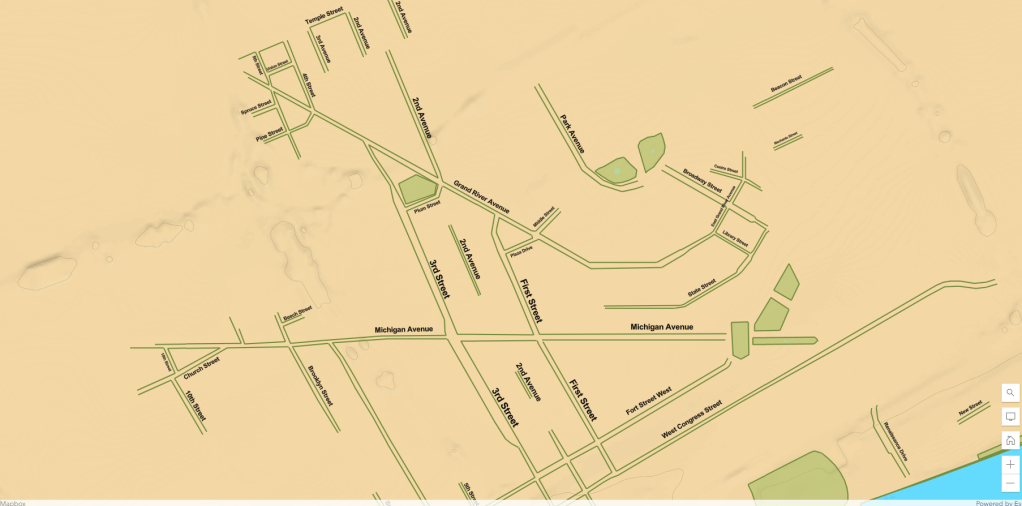

This map shows what downtown Detroit would look like if you erased the streets and street names that honor the colonizers. While in no way parallel to hundreds of years of human, land, history, and language theft and erasure, may this map give you pause to acknowledge it and to recognize the impact of its inscription on the land.

Map: Downtown Detroit with the street and street names that honor French, British and U.S. American colonizers removed.

Unlike removing monuments or changing the names of private buildings, such as university halls, changing street names is a hard and expensive task and one that, frankly, we do not have the time to organize around given all the other needs of our communities. We also cannot boycott or divest from street names, they are everywhere; on signposts, maps, your ID, your mail, every form you fill out, your online billing statements, your RSVP to the DSA meeting, and many more.

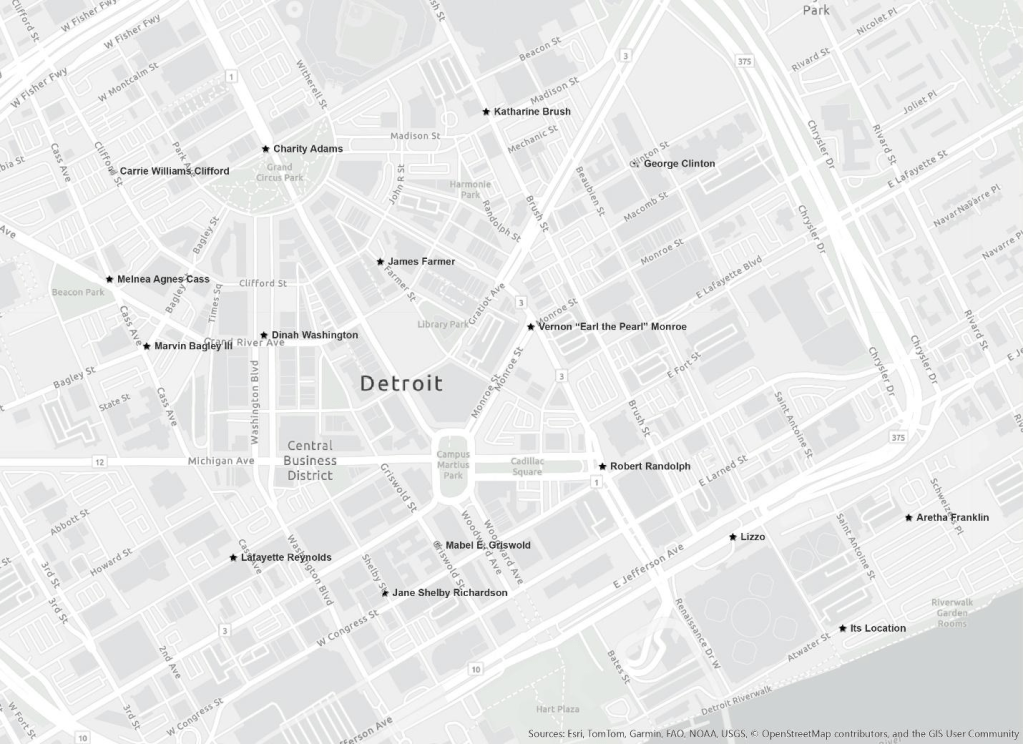

This Gazetteer asks us to change the conversation by subverting the street name narrative to tell another version/s of our shared history…

Map: A New Gazetteer for Downtown Detroit

This project is not intended to be the final word on street names. I am in no way anymore qualified to be naming Detroit’s streets than the city’s so called “founders.” My intention is to inspire Detroiters to use street names to tell different narratives of place that expand our learning of history and thus our vision for the future.

In working on this project, I noticed I was only able to find Black and White honorees for the street names. I want to recognize that this is directly related to the legacies of colonialism and imperialism as discussed above, and to the legacy of slavery, which erased the indigenous names of enslaved people, and replaced them with the names of their White enslavers.

Charity Adams was an educator, soldier, and community leader. Adams studied at Wilberforce and Ohio Universities to become a teacher. On the outbreak of WWII, she joined the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) and later commanded the first Black WAC unit to go overseas. After the war, Adams returned to Ohio to complete her studies and worked at the Veteran’s Administration.

Katharine Brush was a journalist and author. Almost forgotten today, Brush was a critically acclaimed and popular writer during her lifetime. She was best known for her short stories and syndicated newspaper columns, which covered among other things, Ohio college football…and therefore probably Michigan football as well.

Marvin Bagley III is a basketball player with the Detroit Pistons. While perhaps not the greatest player ever to grace a basketball court, naming a street for Bagley represents the importance of recognizing everyone’s contribution to the team. And his career is still young, there is time…

Melnea Cass was a civil-rights activist, suffragette, and labor organizer. Cass worked tirelessly to protest racist hiring practices, register women to vote, and train domestic workers to advocate for social security and other benefits in her hometown of Boston. She also helped found Freedom House to advocate for Black civil-rights and address issues ranging from “urban renewal” to education.

Carrie Williams Clifford was a poet and founder of the Minerva Club, a reading club dedicated to seeking a better world for Black women. She also co-foundered of the Ohio State Federation of Colored Women and actively recruited for the Niagara Movement.

George Clinton “Free your mind….”

James Farmer was a co-founder of CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) and organizer of the Freedom Rides in the summer of 1961. Farmer studied at Wiley College and then Howard University where he was introduced to Gandhi’s teachings. He advocated for and practiced non-violent direct action such as sit-ins and freedom rides.

Carrie Fisher “May the Force be with you….”

Aretha Franklin “R E S P E C T….”

Mabel E. Griswold was an activist and founder of the National Women’s Party in Wisconsin. Following the passage of the 19th Amendment granting women the right to vote in 1920, Griswold and her partner, Elsie May Wood, worked in the Wisconsin Governors’ office.

Melissa Jefferson aka Lizzo is a flutist, rapper, songwriter, and singer. Lizzo was born in Detroit in 1988. Her family moved to Houston, Texas when she was 9. She is the winner of numerous awards including 4 Grammys and a strong supporter of LGBTQ+ rights.

Lafayette Reynolds played by actor Nelsan Ellis (1977 to 2017) on the HBO Series True Blood. Lafayette is a cook and medium who can communicate with ghosts and spirits. Ellis’ portrayal of Lafayette won him a Best Supporting Actor Award from the International Press Academy and millions of fans around the world.

Vernon “Earl the Pearl” Monroe is a NBA Hall of Fame Guard. Monroe scored 17,454 points with the Baltimore Bullets (now Washington Wizards) and New York Knicks during his 22-year career. He won the NBA Championship with the Knicks in 1973.

Robert Randolph is a pedal steel guitarist and gospel band leader. Randolph plays both secular and Sacred Steel, a gospel musical style introduced to into worship in the 1930s. Detroiter, Felton Williams, was one of the most talented sacred steel guitarists. Felton designed and built his own guitars and mentored young musicians in the Detroit area.

Jane Shelby Richardson is a biophysicist. As a child Shelby Richardson was keen astronomer, she calculated the orbit of the Sputnik satellite from personal observation. In 1981, she published her work on The Anatomy and Taxonomy of Protein Structure, which included the Richardson Diagram or ribbon diagram method of drawing the 3D structure of protein. Her diagram remains the standard expression of protein structure throughout the world today.

Dinah Washington was a jazz, blues, R&B, gospel, and pop vocalist. Washington called herself the “Queen of the Blues, she was a prolific and influential singer in a variety of genres and her work continues to inspire musicians and audiences today. Washington was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1993.

A version of this article originally appeared in the Detroit Socialist in 2023. Today, as the current Presidential administration embarks on re-naming projects that further a white supremacist version of history, it feels even more important to recognize the impact of street names on our collective understanding of our history and culture.