by: Ted Tansley

Detroit is working its way into making the largest investment in industrial solar that we’ve ever seen. The plan is to be able to power all 127 municipal buildings with solar energy, utilizing 200 acres of land to generate 33 megawatts. This is a win for the city’s sustainability efforts by reducing reliance on fossil fuels, encouraging local clean energy development, and getting our city closer to reaching carbon-reduction targets.

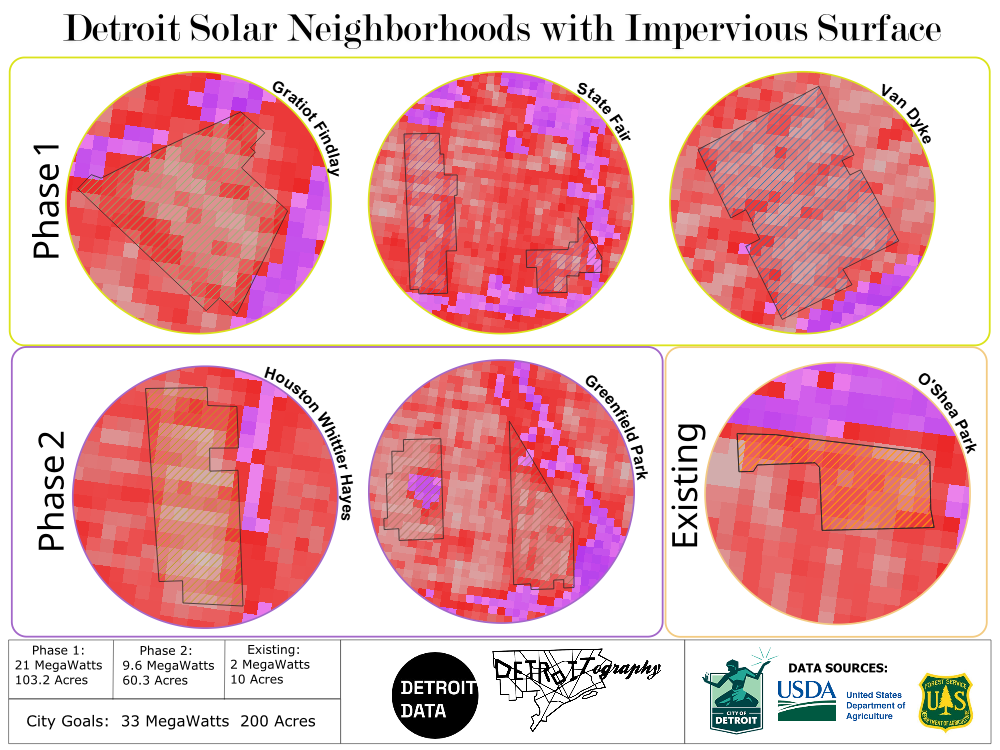

The current plan is to install solar arrays in two phases; the first phase in three neighborhoods covering 103.2 acres and producing 21 megawatts and the second in two neighborhoods covering 60.3 acres and producing 9.6 megawatts. By contrast, the 2017 O’Shea Park array covered just 10 acres and produced 2 megawatts — making the solar neighborhoods project more than 15X larger than our city’s only other solar investment.

To demonstrate the scale of this development, let’s look at the solar arrays laid over downtown and Belle Isle.

Given the size of these installations, understanding their environmental impact is crucial for the city to make equitable decisions that benefit residents and communities surrounding these installations, beyond the city’s clean energy goals. Previous studies indicate that the impact of solar arrays on ambient air temperature is highly nuanced, varying significantly based on factors such as installation type, solar panel construction, local climate conditions, geographic location, time of day, and the original ground cover, among others. This wide range of variables complicates definitive statements about their precise impact on ambient heat in their installation environment. What remains consistently understood, however, is that solar panels inherently absorb solar energy, and a significant portion of this absorbed energy dissipates as heat into the surrounding environment. The specific difference in impact largely stems from what is underneath the panels, as this dictates how much heat is comparatively absorbed by the underlying ground cover versus the solar panels themselves.

While increasing clean energy like this is a win for addressing municipal dependence on fossil fuels, it is worth continuing the discussion about how this investment will impact the communities in which they will be installed. I mapped out these solar installations and published them for public access. You can see details on each installation’s acreage usage, expected megawatt generation, and city-labelled neighborhood name by checking out the full dataset on the DetroitData open data portal.

I further reviewed the solar neighborhood locations based on afternoon heat index, tree canopy, and impervious surface to get a better understanding of these locations as it relates to the current environmental state while comparing it to the existing O’Shea Park solar installation. The maps reveal an alignment between existing heat, sparse tree canopy, and a high concentration of impervious surfaces. This helps us identify opportunity spots to mitigate heat through targeted intervention in these communities as the city proceeds with solar development.

Even though the heat generated by solar arrays is less significant than the urban heat island effect caused by parking lots, streets, and other impervious surfaces, it is important for the City of Detroit to monitor their impact. Proactive measures should be taken in the surrounding communities—not only to prevent any localized heat island effects from disproportionately affecting residents, but also to implement broader strategies that reduce the existing urban heat island effect of the built environment.

Pingback: Detroit By The Numbers: July 2025 Data Roundup | DETROITography

Pingback: Detroit By The Numbers: August 2025 Data Roundup | DETROITography